Malcolm Cecil (January 9, 1937 – March 28, 2021)

Read NY Times obituary here

The journey from England to Saugerties seems straightforward enough. Heathrow to JFK, then a straight shot up the Hudson. For Malcolm Cecil, whose contributions to 20th and 21st century music are incalculable, it didn’t quite happen that way. He took the roundabout route, through South Africa and California, with stops along the way to create, with a partner, the megasynthesizer called TONTO, which as it reaches its silver anniversary still staggers the imagination as much as it did at its birth, and to work with a variety of artists, perhaps most significantly Stevie Wonder, whose most creative period evolved from working with Cecil and TONTO.

Drawn to both music and electronics from an early age, Cecil got his first electronics training as a radio technician in the British military, and his early musical exposure as a standup bassist with the blues (Alexis Korner’s pioneering band Blues Incorporated, which occasionally featured a young Mick Jagger), jazz (Ronnie Scott’s famous London jazz club, where he was the house bassist) and symphonic (the BBC orchestra, where he was the youngest principal instrumentalist in their history). Health issues took him to South Africa, and an invitation to join nightclub chanteuse Lainie Kazan’s band brought him to the West Coast, where he stayed for several years before moving to New York.

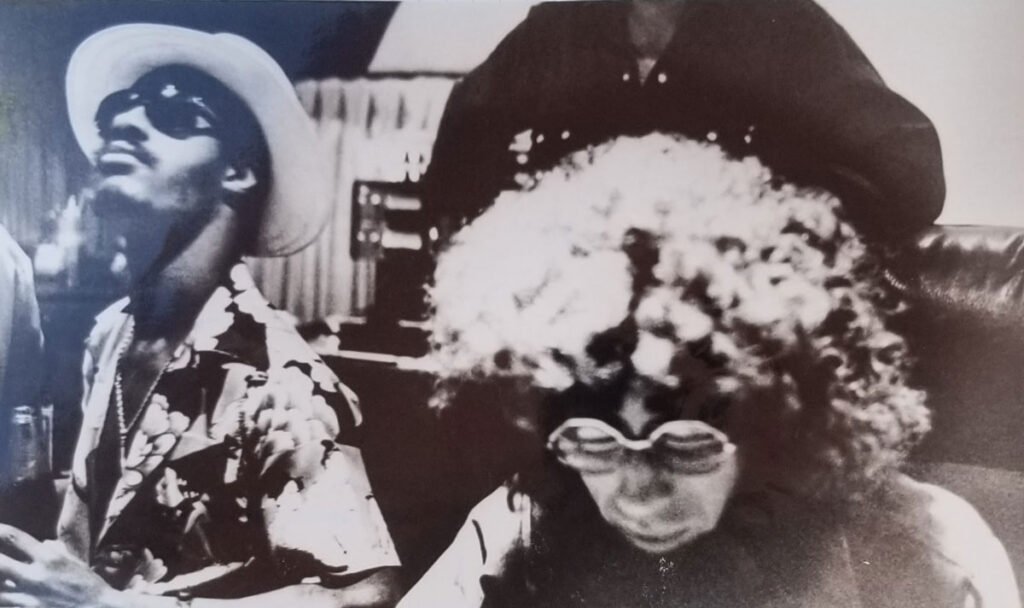

Malcom with Stevie Wonder

In New York in 1968, he worked at The Record Plant, an innovative recording studio, where a friend, Ronnie Blanco, first invited him up to Saugerties. At the same time, he and a friend, Robert Margouleff, started working on an electronic sound synthesizer that would be, in Margouleff’s words, “the first real-time performing electronic music instrument,” or, in more technical jargon, “the first, and still the largest, multitimbral polyphonic analog synthesizer in the world.” TONTO, or The Original New Timbral Orchestra, made its debut in 1971, on an album by Cecil and Margouleff, Zero Time, by TONTO’s Expanding Head Band. Not many people listened to the album, but one who did, and was blown away, was Stevie Wonder. TONTO, and Cecil, became key ingredients, in what many consider to be Wonder’s greatest period—the albums Music of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions, and Fulfillingness’ First Finale.

Cecil worked with Wonder for a decade and a half, and also with other artists like Devo, the Isley Brothers, Gil Scott-Heron, Billy Preston, Weather Report, and many others. Physically as well as tonally striking (it is a 20-foot semi-circle of curving wooden cabinets, with a dizzying array of knobs, dials, sliders and cables), TONTO had a featured role onscreen, as well as on the soundtrack, of the Brian dePalma film Phantom of the Paradise.

Cecil continued to visit Saugerties, and in 2000, after the World Trade Center bombing, he and TONTO moved up here full time. Cecil has stayed, although TONTO has moved on. In 2013, it was sold to Canada’s National Music Center in Calgary, Alberta.

Even without TONTO, Cecil’s Malden studio is a cultural center for both musical and electronic creativity. Cecil hopes that after he is gone, its ultimate disposition will be as a national historic site, supported by the African American music community. He is currently working on a project to collect and present all of the written and recorded work of Gil Scott-Heron, with whom he was a business as well as creative partner for many years.

A conversation with Cecil is almost inevitably far-reaching and mind-blowing. It can flow from the poetics of Gil Scott-Heron to the politics of the music business to the physics of different sound waves and their effect on the sounds of instruments, presented in intricate, but anything but mind-numbing detail–you can actually understand it all. In short, Malcolm Cecil, craggy, British-inflected, gracious and polymathic, is a human TONTO.